Introducing hasql-queue

I’ve recently released hasql-queue, a PostgreSQL backed queue for the hasql ecosystem.

hasql-queue began as a port of postgresql-simple-queue but has evolved a new interface and many performance improvements.

An Overview

hasql-queue is a high performance PostgreSQL backed queue library. It has 6 variations of a similar API. It has two modes of operations: a high throughput polling based API and low throughput notifications based API.

Each mode, high throughput or low throughput, has three related APIs: “at most once”, “at least once” and “exactly once” versions.

You would use the “at most once” API if you are dequeuing items and sending them over an unreliable channel or if the messages are time sensitive and you can afford lost messages.

You would use “at least once” semantics if you are dequeuing elements and want to make sure they are received by another system before they are removed from the queue.

hasql-queue “exactly once” APIs could be used to move elements from the queue’s ingress table to a final collection of tables in the same database.

Out of the six versions the “at least once” notifications based API is probably the most useful.

The High Throughput API

The high throughput “exactly once” API is the basis of all the other APIs. It has the following functions.

The API has an enqueue and a dequeue function. Both enqueue and dequeue can operate on batches of elements. Additionally as is customary with hasql one must pass in the Value a for encoding and decoding the payloads. The ability to store arbitrary types is a performance improvement from the postgresql-simple-queue which used jsonb to store all payloads.

Crucially, the API’s functions are in the Session monad. This is valuable because we can dequeue and insert the data into the final tables in one transaction. It is in this sense that it has exactly once semantics. This is not surprising. One would expect a message moved from one table to another table in the same database can be delivered exactly once.

Schema

For the API to be useable, a compatible schema must exist in the database. To help create the necessary tables, the Hasql.Queue.Migrate module is provided.

Here is the schema migrate creates:

CREATE TYPE state_t AS ENUM ('enqueued', 'failed');

CREATE SEQUENCE IF NOT EXISTS modified_index START 1;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS payloads

( id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY

, attempts int NOT NULL DEFAULT 0

, state state_t NOT NULL DEFAULT 'enqueued'

, modified_at int8 NOT NULL DEFAULT nextval('modified_index')

, value ${valueType} NOT NULL

);

CREATE INDEX IF NOT EXISTS active_modified_at_idx ON payloads USING btree (modified_at)

WHERE (state = 'enqueued');Notice the valueType must be passed in and match the Value a that is used in the API above. For instance, for Value Text a text type should be used for valueType.

For the high throughput API, only the enqueued state is used (We will come back to failed).

postgresql-simple-queue used to use a timestamptz to determine the oldest element to dequeue. However, the performance of timestamps are slower to generate sequences of int8.

Like postgresql-simple-queue, hasql-queue uses a partial index to track the enqueued elements. Unlike postgresql-simple-queue it creates the partial index.

This is the minimal recommended schema. The actual payloads table one uses could have more columns in it, but it needs these columns and related DDL statements at a minimum. For instance, one could add a created_at timestamp or other columns.

enqueue

Under the hood enqueue has seperate SQL statements for enqueing a batch and enqueing a single element. The sql for enqeueing multiple elements is:

where the argument $1 is a an array of elements. However, for a single element, the following is used because it is faster:

I have no idea why passing in 0 instead of using the default value is faster. It is barely faster, like a few percent, but appears to be measurable.

dequeue

dequeue has the following SQL for batches:

DELETE FROM payloads

WHERE id in

( SELECT p1.id

FROM payloads AS p1

WHERE p1.state='enqueued'

ORDER BY p1.modified_at ASC

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED

LIMIT $1

)

RETURNING valueThis is not the most straightforward way to write dequeue. However this is a fast way to write dequeue. It utilizes UPDATE SKIP LOCKED a PostgreSQL feature added to support work queues like hasql-queue.

UPDATE SKIP LOCKED takes row level locks, but as the name suggests, skips rows that are already locked by other sessions.

While the locks are held the row is deleted and returned.

It has the following plan

Delete on payloads

-> Nested Loop

-> HashAggregate

Group Key: "ANY_subquery".id

-> Subquery Scan on "ANY_subquery"

-> Limit

-> LockRows

-> Index Scan using active_modified_at_idx on payloads p1

Filter: (state = 'enqueued'::state_t)

-> Index Scan using payloads_pkey on payloads

Index Cond: (id = "ANY_subquery".id)An alternative implementation I explored was to mark entries as dequeued and drop table partitions instead of deleting. This is slightly faster but is much more complicated to manage so I decided against using it.

The sql for the single element version is identical but instead of $1 uses 1. PostgreSQL is able to reuse plans for stored procedures that take in zero arguments, so inlining the 1 and using a specialized version is slightly faster.

Also we can get a simpler plan for the single element dequeue:

Delete on payloads

InitPlan 1 (returns $2)

-> Limit

-> LockRows

-> Index Scan using active_modified_at_idx on payloads p1

Filter: (state = 'enqueued'::state_t)

-> Index Scan using payloads_pkey on payloads

Index Cond: (id = $2)Benchmarks

The performance of hasql-queue is dependent on the hardware and the PostgreSQL server settings.

For inserts, the speed of fsync is very important. Running pg_test_fsync gives:

Compare file sync methods using one 8kB write:

(in wal_sync_method preference order, except fdatasync is Linux's default)

open_datasync 7403.941 ops/sec 135 usecs/op

fdatasync 7146.863 ops/sec 140 usecs/op

fsync 6269.116 ops/sec 160 usecs/op

fsync_writethrough n/a

open_sync 6611.416 ops/sec 151 usecs/opThis is on MacBook running Ubuntu in VM. These are way better numbers than what you’ll see on most network drives, e.g. “the cloud”.

In other words, if you have very cheap hardware on AWS you will not see numbers this high.

The DB was seeded with 20,000 entries.

| Enqueuers | Dequeuers | Enqueues Per Second | Dequeues Per Second |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1800 | 1710 |

| 1 | 2 | 1784 | 2117 |

| 2 | 2 | 2916 | 2298 |

| 2 | 3 | 2692 | 3024 |

| 3 | 3 | 1402 | 1275 |

| 2 | 4 | 1765 | 2098 |

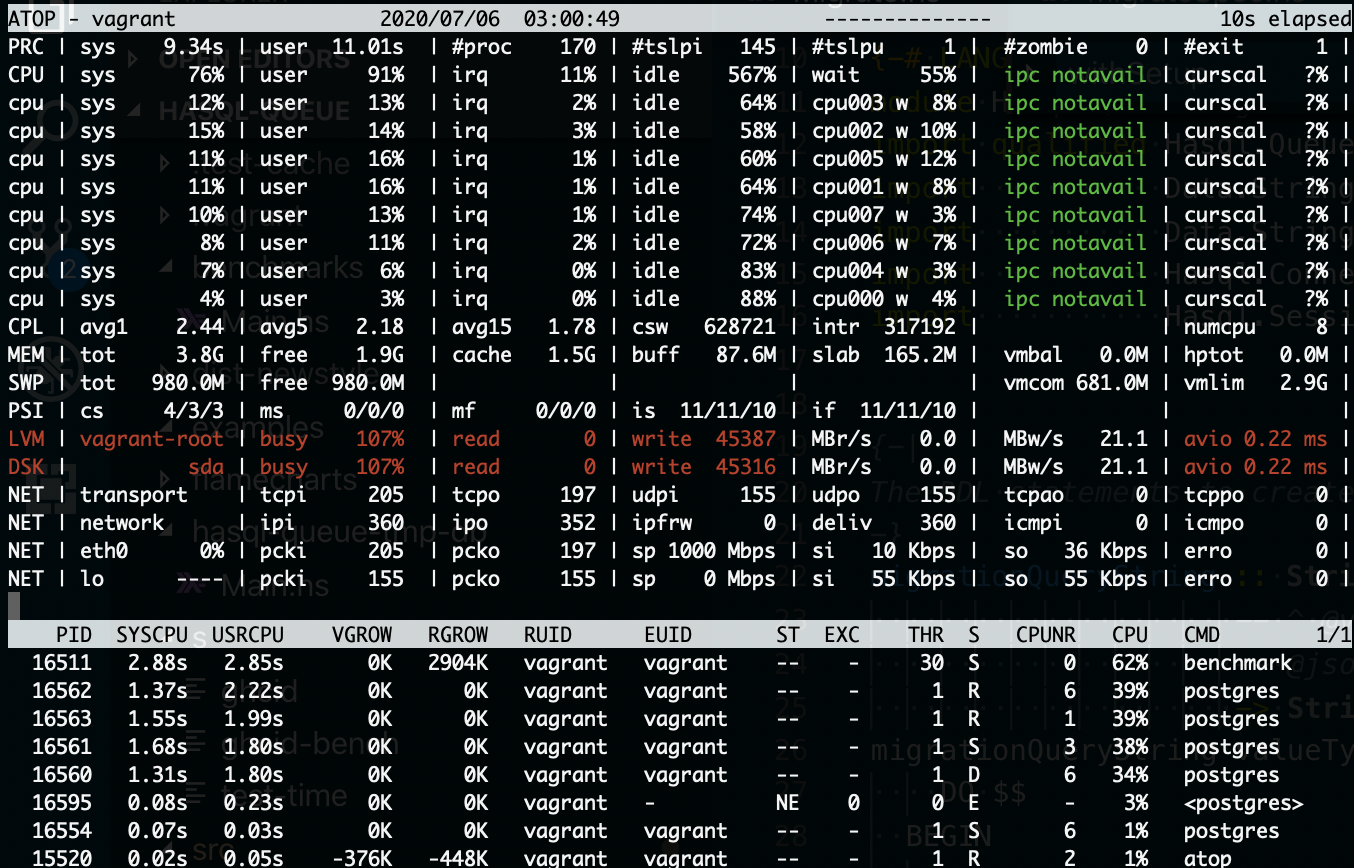

When looking at atop we can see the benchmark is IO bound. One would assume the benchmark would be IO bound if the queries have been properly optimized.

These benchmarks are for enqueueing and dequeueing a single payload. Using the batch API is more efficient but not always possible. I’m too lazy to make the batch benchmarks at the moment.

Low Throughput At Least Once API

When the throughput of enqueuing is high it is most efficient to continuously poll the database for more data. However if the throughput is low, polling is wasteful.

The low throughput APIs utilize PostgreSQL notifications to allow for low latency responses without the resource usage of polling.

Let’s look at the “at least once” low throughput API:

enqueue :: Text

-- ^ Notification channel name. Any valid PostgreSQL identifier

-> Connection

-- ^ Connection

-> E.Value a

-- ^ Payload encoder

-> [a]

-- ^ List of payloads to enqueue

-> IO ()

withDequeue :: Text

-- ^ Notification channel name. Any valid PostgreSQL identifier

-> Connection

-- ^ Connection

-> D.Value a

-- ^ Payload decoder

-> Int

-- ^ Retry count

-> Int

-- ^ Element count

-> ([a] -> IO b)

-- ^ Continuation

-> IO b

failures :: Connection

-> D.Value a

-- ^ Payload decoder

-> Maybe PayloadId

-- ^ Starting position of payloads. Pass 'Nothing' to

-- start at the beginning

-> Int

-- ^ Count

-> IO [(PayloadId, a)]

delete :: [PayloadId] -> IO ()The API is a lot more complicated.

Instead of dequeue we have withDequeue. withDequeue uses a transaction and savepoints to rollback the effect of dequeueing if the IO b action throws an exception. withDequeue will not complete the dequeue operation unless the IO b action finishes successfully. Instead, withDequeue will retry the IO b up to a max amount if an IOError exception occurs. withDequeue will record each attempt and if the max amount is hit will set the entry’s state to failed.

withDequeue could end up dequeueing the same element multiple times, so whatever system one is coordinating with must have a mechanism for dealing with duplicated payloads.

The reason hasql-queue gives up after some number of attempts is to prevent an error inducing entry from stopping dequeue progress.

The failed payloads can be retrieved with the failures function and permanently removed with the delete function.

Benchmarks

The notification based APIs are based on the high throughput APIs and thus inherit the same optimized plans. However using notification introduces overhead as one can see in the following benchmarks.

| Enqueuers | Dequeuers | Enqueues Per Second | Dequeues Per Second |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1741 | 946 |

| 1 | 2 | 1436 | 1546 |

| 2 | 2 | 2264 | 1233 |

| 2 | 3 | 1995 | 1656 |

| 3 | 3 | 2117 | 1280 |

| 2 | 4 | 1514 | 1758 |

At some future point I should show what the CPU and IO load is of a small number of payloads using the low throughput API. This is the real value of the low throughput API: minimal load under moderate usage.

Final Words and Future Work

If you are using a TQueue in a webserver you might want to look at hasql-queue. Designing webservers so they are stateless and relying on a durable persistent state (a database) is great way improve the reliability of your platform.

hasql-queue might not be a fit for your use case, but I would not hesitate to look at the SQL and schema that is used and copy what works for your situtation.

In the future I would like to provide an adaptive API that can choose between polling and notifications based on the level of traffic. Additionally, including the notification in the payload could make the low throughput “at most once” a lot faster.